What makes a city generous to its passers-by? Speaking with Tobias Berger and Daniel Szehin Ho, Thomas Heatherwick reflects on how emotion, function, and detail come together to shape urban life. From the transformation of Pacific Place in Hong Kong to projects across Asia, he talks passionately about engaging the senses and advocates for an architecture that sustains public life through care and curiosity.

Tobias Berger:

Let’s start with a Hong Kong project: Pacific Place re-opened about ten years ago, after four or five years of negotiation. It was an older, more generic shopping centre – and then Swire brought you in. What was your brief actually?

Thomas Heatherwick:

Interestingly, the chief executive of Swire at the time had been there for 20 years, and he was instrumental in building Pacific Place in the beginning. He did something that was quite scary for me, because he said, ‘First, have you done a retail project before? No? Perfect. That’s what I want.’ He then said, ‘Look, I don’t know what we need. Maybe we just need a bit of new paving, but I would love for you to just come and look, and tell me what you think.’ So we came and spent a few days exploring. In a way, Pacific Place is like a small town, with all the complexity of how it relates to the mountainside that it’s built into, and its many floor levels that connect and stitch in the way that Hong Kong does – that lovely, almost hive-like complexity. It isn’t just buildings sitting on flat ground.

At the end, he asked, ‘So what do you think?’ I knew in effect I had someone who was proud of what had been created, saying ‘What’s wrong, what’s with me and with what I've done?’ Now, the way we work is to analyse and see problems – and I see that not as a negative but a positive thing. Thus it was interesting needing to trust him and be frank with him about the things that we thought we could take to another level.

Pacific Place had been very successful and was loved for its calm atmosphere. We realised we could make it even calmer – and bring together things that you might not have had the chance to do when you are building something for the first time. In the end, instead of just replacing some paving, we had a whole new identity – new buildings together with improvements in the ecological performance of the project. We built a new hotel that’s within what had been the loading bay, which became the Upper House – we designed the outside of that.

I’m interested personally in the way that cities and governments used to build public space. After the Second World War, governments used to create the space for society to come together. Then, in many parts of the world, that went a bit wrong and cities lost their confidence. In a country like the UK, there used to be many architects within the planning departments. Now they’re all gone, and it is down to private developers to make the public world we live in.

I know in the world of architecture, ‘culture buildings’ are fetishised – the opera houses, concert halls, and major national libraries. Yet for me, culture is everything around you: it’s the waste depot where you take your sofa or refrigerator to at the end of its life; it’s the hospitals, care homes, community centres...it’s the places where you buy your food and go for dinner with your family and so forth.

So I felt that architecture shouldn’t be seen as the obvious arts buildings. It feels so obvious when you say, ‘Oh, it’s an arts building. Make it artistic.’ Well, some of the most loved buildings in London, in the UK, in Europe, are old industrial buildings – the equivalent of an IKEA shed from 180 years ago, so why can’t everyday buildings connect to us?

Pacific Place was a place and a project, with an amazing commissioner who let us think about the emotion of users and how people come together. In the UK, you might think, ‘Ugh, a shopping mall!’ But in a subtropical climate where it’s too hot to be together outside for many months of the year, where do you come to go on a date if you’re a teenager? Where do you go in order to just be in public space and not cooped up in tiny apartments? Places like shopping malls are major public spaces for everybody – and people’s lives have been lived over the years through them.

I’m therefore quite emotionally engaged and excited by the places where we live our lives. If cities aren’t making them anymore and developers are – special property developers, like the man who led Swire, who’s a friend – they also taught me so much about human behaviour. People who own land in the long term – not short-term building things, selling them, and getting rid of them – long-term people have to think about the whole of people’s lives, about real, deep, long-term value, and about how you use money in the most meaningful ways for us in society.

I’m really interested in that chemistry and in the mix of things we do in the studio, and in that sense the Pacific Place project was very influential.

When I ask anyone from Hong Kong about what they think of the Pacific Place project, they’ll say the toilets and the lift button. Things like that – and one might think, ‘What??!!’

When the project was first being built, the lifts and the toilets were the first bit to be finished. People would say, ‘Don’t worry about the toilets. We’ll do the toilets, and then you focus on the main thing.’

Yet I knew that toilets are a place unlike the main public spaces. Out there, often you are with a friend or walking around, and human nature is that when you are with someone – we are so funny, humans – we are actually thinking about what other people are thinking of us all the time. Thus you’re often not perceiving the environment because you are tuned into the other person. But when you go to the washroom, you are generally by yourself – and you are much more perceptive. So I thought: instead of an opera house, instead of an art museum, what if we put the same love that you would put into the toilet cubicles?

Tobias Berger:

You revolutionised the toilets in Hong Kong. I don’t know if you’re aware of that, but they have been copied now in other shopping centres – it really changed how shopping malls perceived that place.

Thomas Heatherwick:

Well, if the effort is copied, I’m really thrilled.

In Pacific Place, we were keen to soften the feeling – it had been very hard and sharp. We were torn because toilet cubicles need doors, doors have hinges, and hinges are not curved or soft. We were thinking we could make curved doors, but then thought we can’t have a curved door and then a sharp hinge.

Emotionally it doesn’t feel right – like you’re faking something. Therefore, I thought, ‘Well, really, you want the wall to bend. Could we make a wall bend?’ It sounded so ridiculous. I remember presenting it to the chief executive who’s just an open person, and he agreed – provided we could get that to work.

And so we did – we spent six months.

One other thing that I was really happy and proud about – things which probably nobody notices much but they probably can feel – was on level four, at the drop-off arrival, where there are pavements with drop kerbs. We needed to follow regulations, certainly, but also because it’s the right thing: we needed drop kerbs, or the ability for the kerb to drop to road level so a wheelchair user can cross over parts of the road and be back on the pavement.

Weirdly, the drop kerb was only invented a matter of decades ago, by a disability designer so that wheelchair users could use a city in a similar way to anyone.

However, I always thought drop kerbs look like they wish they didn’t have to do what they do: you can see that they’ve angled the curve down so a wheelchair can go across, and then the kerb lifts up again. Instead, we were thinking of how we could put details that reinforce welcome. We proposed that the kerb comes along the pavement edge and twists down and then twists up – and there are only like nine drop kerbs in the project. They’re sculptural – and carved in Carrara, Italy. Just doing nine of them was not so expensive; instead of feeling like a broken kerb, it feels like the kerb is welcoming you. Something like that is almost invisible, but you can feel the calm because places normally have disjointed details.

With Pacific Place, another detail were the handrails all around. No one has reinvented the escalator, you know: an escalator always has the steps that go up, come round, and come back down, and handrails that go round. Typically, you get a design for the handrail, and then there’s this round end. Normally you just chop it like a loaf of bread and push them against each other. Again, it’s jarring.

What we did was we made the balustrade that comes along and the wood as the same section as the rubber on the escalator, so the escalator shape influenced the balustrades everywhere else. The two come along and end at the same curve, and then one goes off to become handrail, and the other goes off to move again. It’s about calmness – and a version of minimalism – trying to make things feel they come through with the same energy.

Tobias Berger:

Yet it needs a lot of detailing, research, and just understanding this situation. I’m quite interested about your research process: your projects like Azabudai Hills in Tokyo or Pacific Place in Hong Kong all have a landscape that is very much thought through – like the details we’re talking about.

Thomas Heatherwick:

We have a landscape team in the studio because I’ve learned over my 31 years of having the studio that more than ever, you can’t separate how a building is an object and how a building is part of a tapestry of streets and the surrounding landscape – and how you stitch those two together.

The first thing you see is landscape, not building. I’ve been equally interested in trying to soften the hardness of buildings – because buildings worth doing by the construction industry need to be big these days, and you don’t get small buildings in general anymore unless it’s someone’s private home.

The real changes of cities are done at a big scale, with the challenges of bigness. Within all my projects, I’m working to counteract the inhuman factors that bigness throws up: too much monotony, too much repetition, and an absence of visual complexity necessary to feel nourished.

The integration of nature is one way to create more visual engagement and a diversity of fascination for somebody visiting. From a research point of view, our processes begin as we start, through conversation, and we try to fully understand the site and the needs of a particular project. Furthermore, the person who’s commissioning you is normally an absolute expert at many things to do with the project you were about to do.

Thus we try to learn from them and understand everything that’s on their mind. We can seem as if we are the authors, but really, they are – we are a tool to achieve their outcome. Normally, they have a very strong sense of what something should be or shouldn’t be, while our process is very exploratory: we try lots of things, gradually narrowing down and eliminating from our inquiries things that don’t feel quite right. In no way is this a sole authorship mindset.

At the root of much of what the studio does is a belief in functionalism – but when we say ‘function’, emotion is also a key function. We have had places that claim to be functional but don’t function on an emotional level. Given that buildings are predominantly for humans, it’s not a functional building if society doesn’t care.

We try to analyse our own responses to a place and to see it through our pre-designer self – almost tuning back to your inner eleven-year-old, which we all have, thinking of how they see and feel the world, how they wonder things they wonder about, and what they are confused about when they look and can’t figure out ‘why did somebody do that?’.

We look both through a professional lens but also try to put ourselves in the shoes of a passer-by. We have been developing that muscle – which often is lost as people professionalise. Inadvertently, it’s easy to become part of an echo chamber that thinks sees itself as right and that isn’t constantly double- checking: ‘Hang on, what would an eleven year old think? Forget what we all think is clever – how would somebody new to this respond?’

Not that you can make everybody happy – but some buildings and places make almost everybody unhappy! Still, we need to be much better at tuning into how we can make places that are at least engaging and not boring people. It’s a funny word, ‘bore’, but we talk too much about beauty. There are places I love that are certainly not beautiful, but they are engaging and fascinating.

The characterisation of what society needs is everything to be beautiful – I don’t fully buy into that – but I think we do need places to be engaging and have the potential to be interesting to us in multiple ways.

Tobias Berger:

And do you think that there’s a difference between doing that in the Western context and in Asia, with a different idea of public space, social systems, and so forth, as many of your early projects were in Asia?

Thomas Heatherwick:

All over the world, we have a universal thirst and hunger for places that are generous to people and to society. I believe we’ve been undersupplied with places that feel welcoming and open – that feel inviting even if you don’t work or live there.

I got interested in the word ‘passer-by’ because I feel we’ve neglected them. We have people talk in the construction industry about our ‘clients’ all the time, as if that’s the only people you are making happy – and forget that we also have this other client that’s called society, the ‘passer-by’ who will never go inside what you do.

I also have a deep belief that we have these eight billion people on the planet where every single one thinks they’re special. In a sense, we are all special. Obviously, there’s a paradox: if there’s 8 billion of us, are we special?

There are so many places that treat us as if we are not special. When you work on a project, you need to affirm to people their own uniqueness somehow.

We’re both unique and phenomenally similar – those two things coexist. So I think that there are universal similarities across us all over the world.

For me, it’s hard to differentiate real differences in mindsets in Europe versus North America or Asia. Yet I find there is much more receptiveness from governments and development teams elsewhere, openness to ideas that are more unexpected, and understanding why something matters – and it isn’t vanity. We’ve got a whole lexicon of put-downs for projects that are ambitious, as well as delusions of sophistication that, I think, are understandable in a cultural cycle that we are in in Europe as a much older modernised culture, but act against us in making us think that we have the answers more than we really do.

I think that the ambitiousness and hunger that I’ve experienced in Asia has allowed us to make projects that push forward.

The simplest example is the Seed Cathedral, the UK Pavilion at the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai, where we had half the budget of the other Western nations. The British government was terrified that what we were doing would not be understood by a Chinese audience because it was not showing castles, queens, Sherlock Holmes – not trotting out clichés but showing something even British people haven’t seen, which is a major chunk of the Millennium Seed Bank collection.

The Seed Cathedral won the top prize at the Expo. One of the smallest pavilions, it was a strategic use of the money. It was interesting arguing to the British government that what they thought was risky was the safest thing we could do – because if we made something that was cheesy and clichéd when a visitor was choosing which of the 250 pavilions to spend three hours queuing up for, they’re not going to pick the ones that are predictable.

There are universal truths, which is that we as people are all hungry for things that have an authenticity, that strive to push forward society, have invention and progress, and relate to our worlds in new ways that feel meaningful.

Our yanking back of ambition that we inadvertently do in Europe is a shame because it acts against us. Things we change and protect are the projects that have come out from the ambition and confidence of the past. Thus cultural confidence is something that is so precious – and has been growing and growing in Asia and diminishing in a European context, which is self-defeating.

Daniel Szehin Ho:

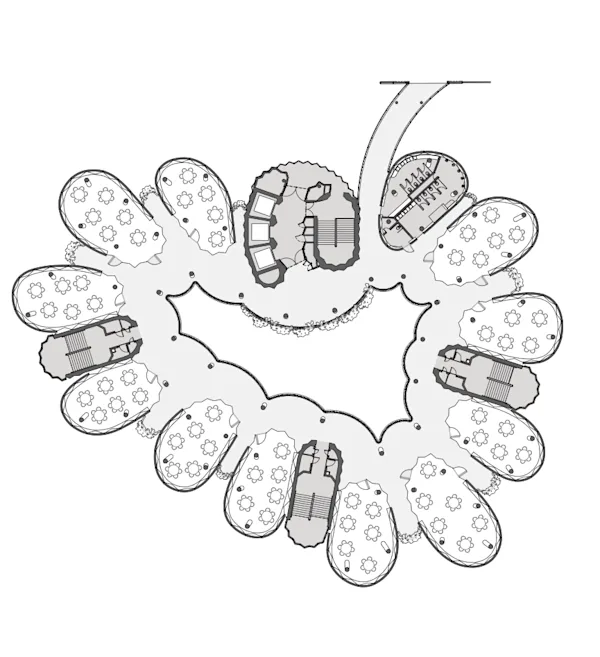

You were mentioning ‘bigness’, and I would ask you about towers and podiums. Dense cities in much of Asia have this development model of towers – sometimes engaging, but often there is a certain boredom to them, repetitive as ‘machines for living’. There’s a podium and then a tower, and while there are many ways a podium can connect better with the street level, how would there be ways to think about the tower? You have taken different approaches with Azabudai Hills in Tokyo and 1000 Trees in Shanghai. Is that a way going forward – beyond the intensity and repetition of numerous towers over a podium?

Thomas Heatherwick:

I’m interested in how we get the necessary density in cities in order to have enough street life – which in turn sustains streets that demand less car use. So the need for not only smaller buildings but taller buildings matters, especially now that we need fewer shops as more things are purchased online. Our streets become dangerous if we don’t have them alive – and shops were one of the main ways to bring life to streets.

The streets are scary when people aren’t there. We’ve got this funny paradox again, because you imagine people are the scary things when it’s absence that scares people.

Towers are quite the glamorous thing; they feel like something that needs strong design, while much less glamorous is your street experience. We have very little expertise in general in the construction industry and in the design side of how we would make streets alive if you don’t have so many shops.

I’m trying to look at this slightly difficult question differently. Partly because in London it’s one of the questions I often get asked, as one of the public figures involved in architecture: ‘What do I think about towers?’. And I keep saying: don’t worry about towers as much. Hong Kong taught me that tall buildings can be fine. The challenges are at the bottom. In an area like Sheung Wan or Wan Chai, there are some really tall buildings, but at the street level, you get enough change and diversity on the street, especially with the chopstick towers – the slim towers. In general, new towers, when not in such precious land as Hong Kong, are fatter; with those fat towers, you get to the street level and all you experience is a dead lobby. You can see that somewhere behind the glass is a marble reception desk – and maybe there’s an artwork so that they seem sophisticated to the clients, but it offers you nothing. It’s not a giver – it’s not fascinating, it’s not generous. It’s got the same door handles as every other office building; there’s nothing to catch your eye.

As someone interested in what purity is, the idea of a tower needing no podium and just shooting down onto the street has total clarity and sounds clean. The stereotype of the cheesy podium with a shopping mall, and then cheesy towers sticking off that, is embedded in our heads.

Human perception is interesting, however – and this is borne out in a few of our recent projects. When you really look at how people experience life on the street level, we don’t really look up as much as we think we do. We really experience the first 40 feet, as we phrased it in our master planning work in San Jose. That’s where your main perception is.

Thus if you are putting love, care, and money into the experience for society, I believe it’s better to put your money into that first 40 feet, because that is where there are places that are deeply unoriginal, deeply mean, too large, repetitive, boring, and unengaging for an eleven year old who never is going to go into that apartment or office building. How do you make that place somewhere a person feels safe chatting to a friend – and not feel they might be robbed?

So I’ve come round to podiums – even though I never thought I would think podiums as a thing that you could care about. I actually see you can’t throw money equally everywhere on projects. How do you find a way forward, then? Some of the buildings from the 1920s and 1930s that I love – and there are examples in North America, in some of the main cities – had towers that really do come all the way down and they aren’t podiums. There’s extra enrichment and fascination, with details, care, and craftsmanship in the doorways, windows, and at the bottom. Then they gradually diminish: from approximately 40 feet upwards, you get a very simple tower – at the top, there’s a bit more love and care. In terms of priorities: I really think that we don’t do enough surveys in order to understand what the public truly notices and feels about places. Yes, we survey people inside buildings, but I find it fairly ludicrous that the best design and architecture firms will proudly say they do post-occupancy surveys, and it turns out they ask questions to understand how the building is really used afterwards only from the users of the building, and not anyone who is just a passer-by.

How do you define users of the building in general? The users of a brand-new building are very lucky people. In almost every new building I go into, the daylight is pretty good; the ceiling height is pretty good; the lobby is pretty good. But are we even interested in the experience for an eleven year old or an elderly lady walking past? Did we actually measure whether they felt that you as an architect contributed something to society on the walls of public life?

These walls of public life are to me the neglected part – and such an opportunity. I know that people who study architecture really care. That’s why they chose a very long period of education and less pay than if you went off and became a banker or so many other professions. But inadvertently in the construction industry, without realising it, people stopped caring. If you really ask them, underneath all this they do care – but the echo chambers and bubbles make us spin off and stop looking the impact of what we do.

Tobias Berger:

Your buildings are so much more than just buildings, right? You think about how people move in them, and you talk a lot about emotion. With The Hive (Learning Hub South) at the NTU (Nanyang Technological University) in Singapore, you even made it open. Do you think that architects and designers should have much more involvement in how these buildings function and work in day-to-day life?

Thomas Heatherwick:

Well, I’ve come to realise that the pressure on architectural teams is massive. Your question is in relation to budget, getting commissions, regulations, safety, and then communication across many consultants, and your ability to inspire cities and property developers – it’s very difficult role. So it’s easy to pile more jobs on – but we do think that in our architectural realm, we are not communicating with the public enough. If the public are more involved, they will talk to us and back us up. What they’ll be saying is this: make places more generous, make places more interesting for all of us, not just the lucky people who are inside.

The more the public are not treated as if they’re ignorant and stupid – which is a weird mindset that some aspects of the profession have got into – the public will move from an embattled desperate position to useful backup, I believe. After all, they’re not going to say to property developers and local authorities, ‘Oh, could you make more boring places?’ Architects want to do interesting things, but it’s actually that the industry gets away with making boring places because society hasn’t got a voice. They think it’s like emperor’s new clothes.

That’s why so many people are so desperate, particularly in the UK, and just wonder, ‘Well, can we just copy the past?’ That doesn’t mean they only love old buildings. It’s because that’s something you can point to that you could describe as characterful and soulful in some way – but I don’t believe you have to copy the past.

You can make good projects that have texture, character, and emotion without copying the past. For instance, if you ask the public what their favourite building is, they will say many modern buildings, not just old ones. Don’t be scared of the public, I say. I feel we’re scared somehow that the public will just say they want silly stuff, but I don’t believe that’s true.

Daniel Szehin Ho:

When you talk about ‘city level’, ‘street level’, ‘door level’, one gets the sense you bring a design mindset in thinking about the overall conditions – on some levels it’s really like urban planning, right?

Thomas Heatherwick:

In our work, we are getting chances to design districts. Last year, we did last year a six and a half million square foot development. The Azabudai Hills project is of a significant scale, and we are working on a number of major district projects, where you are needing to think at the largest city distance, street distance, door distance.

I’ve always found master planning a funny thing because I’ve seen so many places where they’d say this is a good master plan – yet if you make boring buildings in a good master plan, it’d still feel soulless. You are torn: is it better to have engaging, soulful, textured buildings in a bad master plan? It probably is, because we humans are incredibly adaptable. We work in and around things, whereas there is room for much more legislation and policy that advocates for fascination and absence of boredom. When we talk about beauty, it feels like very subjective – and we can protect ourselves by saying that we can’t have a conversation about beauty with people.

Boredom isn’t entirely subjective. When you do surveys with the public, find that over 90% of people all agree what boring is. In the Humanise campaign and the book we wrote, it’s really not about advocating that buildings should be all curvy, or all square, or old-fashioned or cyber, or all covered in trees. I don’t really mind any way, but I do believe that society needs buildings to offer more visual nutrition.

We are now learning as we are starting to understand our brains more that our brains need visual complexity. Every few seconds, we need millions of bits of information. If you starve the brain of that visual complexity in the public context, you go into stress. It’s weird.

You imagine that less means calm, but in streets it doesn’t. In our streets and cities, with less, with monotony or endless shiny, serious, smooth, plain environments, your body goes into stress. Your level of cortisol rises and that’s what there is starting to be some research – which is ridiculous for an industry that is as big as oil and gas, to be only beginning to measure its real impact on society.

We’re in a very exciting time. I hope it will lead to what will support millions of designers, urbanists, and architects who want to do good things, who feel that the pressure on them to be cost-effective.

Society says: spend a little bit more to make your building well insulated, and spend a little bit more to generate alternative forms of energy to have a low-carbon building. Yet we don’t have equivalents for visual engagement because there’s no public conversation about how your building is generous to society – as a wall of public life.

People say, ‘Oh, a sense of place matters.’ That normally tends to mean sculptures or trees outside boring buildings – and that matters a lot, too. But the full picture is all of these. You can’t ignore the gigantic walls of public life that are the surfaces of buildings, and somehow we are in denial of something that’s very simple.

Daniel Szehin Ho:

Your pointing out the difference between beauty and boredom is helpful, because sometimes in Asia – I’m thinking of Hong Kong, maybe also Bangkok – on the street level there are parts I wouldn’t call beautiful, but very engaging in a weird, interesting way.

Thomas Heatherwick:

Like Sheung Wan, it can be positively stinky! You walk along, seeing all the dried fish everywhere – but it is joyful and it really makes you feel alive to be there. You wouldn’t necessarily say it’s beautiful, but it’s one of my favourite places in the world! There’s less fish drying now but it’s still got texture, and that fascination is necessary if we are going to make places that we care about, so that we do not knock them down all the time.

Your readers and listeners may be there thinking, ‘Oh, you’re just trying to make everything nice – that’s not really the biggest, most pressing issue of our time.’

I understand someone saying that. However, our dirty secret in the industry is the carbon involved in making buildings. The carbon from flying that society talks about amounts to about 2.1% of greenhouse gas emissions. But construction – constructing boring buildings, knocking them down, building more boring buildings – is five times that and we don’t talk enough about it.

The part I find quite uplifting is that you suddenly realise sustainability ultimately comes down to love; it isn’t a metric in a conventional way. What really sustains things is if people care about it – and want to repair, adjust, and adapt it.

Tobias Berger gestures at the model of a London double-decker bus inside Heatherwick Studio.

Tobias Berger:

I haven’t taken a London double-decker bus. And Hong Kong, of course, has these amazing double-decker trams that I take all the time.

Thomas Heatherwick:

Those were an inspiration for us while working on the London buses.

The Hong Kong trams have two staircases; your old buses in London only ever had one. In Hong Kong, you have this tiny tram, you have two staircases, and you use them. It proved to me that you can create something that’s soulful, even in a tiny space.

Then there is the use of wood, metal, the sliding windows...the seeming impossibility, structurally speaking. When you stand back and look at them, you think: where are the wheels? And then you think, how do they stay up? Especially because there are typhoons in Hong Kong...To me, they are just wonderful and I hope that they’ll never stop running.

Tobias Berger:

No, they won’t let them stop – the star ferries, and the ding dings – they are just too much part of Hong Kong. Changing the topic a bit: are there any projects in Asia you are looking forward to? Like what’s an ideal project in Asia? A city? A tower?

Thomas Heatherwick:

I’m really motivated by need and I’m trying to make places that can make a difference to people. I don’t feel I’m expressing just myself as I work with a team of 250 people. So together we will try to think: ‘What are the real opportunities and real needs?’

If I was talking in a British context, one of the most pressing needs is in health. If you want to see the worst of society’s places for itself, you need to look at care homes – this is not a sexy-sounding thing.

If you look at the care homes in the United Kingdom and in many parts of the world – and forget for a moment the elderly people being cared for there and just look at the people who work there – and think: within the nursing system, if you were a nurse, where would you most like to work? You’d probably say with newborn babies or with accidents, exciting parts where you can have a major impact, whereas at the end of life, there would be no miracle recoveries. You’re just helping someone live to their end, the end of their lives, and it’s the lowest-paid aspect of nursing.

And it’s not a great environment. Both my grandmothers were in care homes at the end of their lives, and I was ashamed for what it was saying to the nurse, to the staff who was there. It was confirming to them, ‘Yes, you’re in the worst job.’ Actually, those environments need to be thanking people – that they walk in and there needs to be society saying, ‘Thank you for what you do for us,’ because the one thing we have in common all together is we will all get older.

This is not so glamorous but could make a massive difference. Yet we’ve got an economic model that makes it very hard to intervene. Our economic model loves throwing lots of money at arts museums. Imagine if you just put a proportional part of what got put into a new art museum and spread that across a whole lot of care homes. You could make the best care homes in the world – places that affirmed the amazingness of people’s lives, and the gratitude we have for the people who look after and cherish people at the end of their lives.

In Asia, I would love to work on where you can impact the most people – so the public-facing places. There are different models of healthcare, but health and education are places where you’re setting the scene for people’s lives going forward – and you are giving the chance for someone to see that there are so many different ways to look at the world. Many of us as individuals feel under pressure to conform to how we think the world should be. Projects that affirm that there is another way, that there are moments where we feel like we’re the outsider, places that are designed for the non-fitting-in-ness of all of us – these are, I think, almost the most generous.

Thus I’m most motivated by the things we’ve not done before. I would love to work more in Japan with the phenomenal craftsmanship, working with people in Roppongi in Tokyo. There’re so many cultural references that I feel my job is to amplify rather than ignore and impose something in the Western model.

So, in a sense, I see myself as an amplifier, trying to come find something and enlarge it and stretch it and give it oxygen. I hope that we can develop special meaning for many projects, many decades to come.