I. A Crisis of Coherence

In an age of profound technological and economic upheaval, it is sometimes tempting to retreat into despair, nostalgia, or grief. Yet if alternate pathways of planetary and societal evolution are possible, imagination may be our first step towards reaching them. Imagination does not arrive ready-made: in the hands of artists, it takes the form of disruptions and revelations, exposing what dominant systems conceal. Through form, narrative, and non-conceptual space – where experience exceeds language – we surface fragile alternatives, glimpses of what could be. Only by imagining differently can we begin to build differently.

This call is not a luxury but a necessity, for the accelerating pace of change has begun to outstrip the very concepts that once anchored our world. Chief among them is the Enlightenment ideal of the rational, self-governing individual as the pinnacle of progress.3 That figure now feels increasingly obsolete in a world defined by interdependence and complexity. As the notion of autonomous rational actors dissolves, in its place circulate digital selves that are extracted, flattened, and commodified. Algorithms replicate these avatars endlessly, privileging optimisation over understanding – nuance, contradiction, and depth are stripped away in favour of whatever can be calculated, ranked, and sold.

This misalignment between human and machine goals is not accidental but by design: digital technologies were built less to liberate than to manage, surveil, and control.4 As Michel Foucault observed of the panopticon, surveillance produces a state of conscious and permanent visibility, ensuring the automatic functioning of power5; ‘visibility is a trap’. Today that logic re-emerges in algorithmic governance: data extracted at scale, individuals monitored, profiled, and subtly moulded in ways that are often imperceptible.

Yet this trajectory was never inevitable, for machines were once imagined differently. They were meant to help us become better beings, to expand our capacities rather than constrain them. Early visions cast technology as a liberating force, even as a spiritual proxy for our ideal selves, mechanical embodiments of qualities we longed for but struggled to realise. That aspiration has given way. Today the dominant paradigm is not liberation but control: the drive to optimise and neutralise uncertainty. Contemporary machines, governed by algorithms, aim to minimise risk and regulate behaviour. Rather than nurturing ambiguity, they compress it into categories and metrics. Rather than embracing difference, they standardise. The machine ceases to mirror our highest ideals and becomes instead an instrument of efficiency, a tool for securing order.

To navigate this reality, we need more than critique – we need imagination. We must reclaim agency and rebuild systems grounded in empathy, complexity, and care.

Artificial intelligence is one of the most urgent sites for this reimagining, yet it does not emerge in a vacuum. It unfolds in a world already destabilised by inequality, climate collapse, and institutional decay. In Atlas of AI, the scholar Kate Crawford shows how its infrastructures are inseparable from planetary extraction and labour exploitation – from vast radioactive tailings lakes of rare earth mining in Inner Mongolia to the precarious labour of thousands of data workers in Venezuela and the Philippines, as well as a Google data centre in Oklahoma that consumes millions of gallons of water each day in drought-stricken communities. These infrastructures do not open space for genuine alternatives; they embed the values of the systems that produced them.6

Climate, computation, and capital are converging, but instead of clarity, this convergence deepens disorientation. The ‘smart’ systems we build – from predictive policing algorithms and automated credit scoring to high-frequency trading platforms and military drones – are not designed for connection or curiosity, but for control: to manage risk and maximise return. They do not serve everyone. They serve a narrow and elite group of technologists, financiers, defence contractors, and politicians. These industries promise innovation even as they concentrate power.

We are not training machines for the world we need, but encoding them with the values of the world we already have: extraction over relation, speed over depth, efficiency over imagination.

The story of OpenAI makes this plain. As the journalist Karen Hao shows in Empire of AI, the company became a battleground for these forces – from the dramatic ousting and reinstatement of Sam Altman, to internal clashes between advocates of AI safety and those pushing for rapid commercialisation, to its structural pivot from non-profit idealism to a venture-capital-driven capped-profit model. These struggles expose AI as a site where corporate, financial, and geopolitical power converge.7 Denaturalising technology – tracing its labour conditions, environmental costs, and cultural effects – makes clear that AI is not inevitable, but the result of human decisions; not fate, but an ongoing choice.

This is not only a technological choice but a choice of world-building. What kind of world are we inscribing into AI – and what would it take to reorient its values towards another future? One could imagine systems that do not arrive pre-trained on harvested data, but begin fresh, learning through interaction as a newborn child or animal might encounter the world. Such machines would be companions rather than overseers – growing with us through relation, curiosity, and shared experience. Choosing other paths of machine, human, and planetary evolution could open the door to technologies attuned to care, complexity, and cohabitation – a gesture towards what the philosopher Yuk Hui calls technodiversity, the idea that there is no single universal path for technology but many, each reflecting distinct cosmologies and ways of living.8

II. Intelligence in the Age of Extraction

If imagination opens new paths, we must also look squarely at the conditions of the present. We are told that AI is accelerating, but we rarely pause to ask: accelerating towards what, and for whom?

Beneath the language of innovation lies a familiar structure: not the democratisation of knowledge but the consolidation of power. That consolidation rests on a profound transformation: intelligence, once a shared human capacity, has been remade as a commodity – governed by proprietary code and deployed for strategic gain. What is heralded as the dawn of a new cognitive era is instead an intensification of extractive logic, where AI functions as an architecture of pre-emptive control. Its celebrated capacities – prediction, personalisation, automation – are not neutral. They optimise surveillance, from predictive-policing tools that target certain neighbourhoods to recommendation engines that monetise attention, and to autonomous systems built for warfare. What is marketed as ‘smart’ often conceals something far more violent: a system designed to monitor, classify, and exploit.

Beneath this architecture of control lie unstable foundations. Data is harvested without consent, scraped from online searches, social media posts, and even the traces of our everyday movements. The labour that supports it – tagging, moderating, cleaning – remains hidden and precarious, often outsourced to workers in the Global South. The infrastructures behind it consume enormous resources, with data centres drawing electricity and water on the scale of small cities, alongside the land, energy, and rare earth minerals that sustain them. These resources are often taken from communities already living in scarcity. This is not a temporary disruption but a long accumulation of harm. The cultural critic Rob Nixon calls this dynamic ‘slow violence’: harm that accumulates gradually, disproportionately affecting the poor and marginalised, whose struggles remain invisible to mainstream narratives of innovation.9 Artificial cognition, as it currently exists, is built on this real-world depletion.

As these systems expand, public institutions in the West contract. Education, healthcare, and social services are defunded – not because they do not matter, but because they do not yield profit. In other regions, the issue is less one of defunding than of uneven provision. In both contexts, however, the algorithm becomes the new bureaucrat: unaccountable, opaque, and designed to manage risk rather than cultivate care. We see this in algorithmic triage systems that ration healthcare access,10 predictive tools that allocate welfare benefits, or risk models that quietly shape who receives housing or parole.12

What unites these systems is not only their opacity but their impoverished imagination. This is not simply acceleration but a collapse of vision. AI extends a legacy of abstraction and disembodiment: privileging prediction over understanding, control over contact, and reducing the complex to the computable. What disappears are the textures of embodied life – the warmth of a hand held in care, the smell of a meal in a community kitchen, the rhythm of voices at a rally, or the moment a judge or caseworker grants the benefit of the doubt. These moments of touch, sound, scent, and shared presence are not peripheral but the ground of meaning and connection. When flattened into data, what is lost is our capacity to live and act together in ways that exceed prediction or control.

Where AI abstracts, disembodies, and flattens experience, Yi’s practice pushes back, reclaiming the textures of embodied, sensory life. Her 2015 series of Quarantine Tents, part of the exhibition You Can Call Me F, took the form of transparent enclosures modelled after medical quarantine structures, examining architectures of containment and how the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak became a manic, racialised spectacle. Inside, uncanny objects – tea and kombucha, industrial materials, grooming products – assembled a visual grammar of hygiene and exclusion. Yet the deeper tension emerged through scent.

Infusing each tent was an olfactory mix drawn from two sources: bacteria cultivated from over a hundred women in Yi’s professional network, and air samples from Gagosian Gallery, framed as a symbol of masculine power in the art world. This pairing staged a confrontation between atmospheres. Gagosian’s odourless ‘smell of power’ was institutional and controlled; the feminist ‘super bacteria’ formed a living archive of shared biological material. One evoked sterility and dominance; the other, a microbial commons charged with embodied risk – precisely the qualities algorithmic systems strive to suppress.

Seen from today’s vantage, the Quarantine Tents anticipate a critique of the sanitised and depersonalised logic at the heart of contemporary AI. Such systems prize abstraction over embodiment, flattening messy realities into credit scores or facial recognition templates. Yi’s tents disrupt this logic with intimate contact, turning architectures of containment into visceral sensory experience. In doing so, they press us closer to the questions buried beneath the interface: Who is captured as data? Who is dismissed as noise? Who is coded as a threat, and who remains legible to power?

The project asks these questions directly and extends them further. Through what architectures – technical, institutional, atmospheric – are such decisions made? Not only in servers or source code, but in the very air we breathe, and in the very atmospheres that govern recognition, risk, and power itself.

III. Atmospheric Politics

If power today is exercised through invisible architectures, Yi’s practice makes them tangible in the most pervasive yet least perceptible medium: air. Normally unseen and unreflected upon, air becomes a carrier of memory and conflict in her 2016 exhibition Life Is Cheap,13 where questions of race, labor, and toxicity could no longer be ignored. Yi collaborated with a forensic chemist and perfumer to produce a scent drawn from two sources: the sweat of Asian-American women and the pheromones of carpenter ants. The result was a trans-species, cross-racial atmosphere that had to be breathed.

Inside the gallery, live bacterial cultures from Chinatown and Koreatown grew alongside a diorama of 10,000 ants navigating a circuit board, evoking both invisible labor and unseen toxicity – how racialised work is bound up with environmental risk. This dynamic resonates with the scholar Hsuan Hsu’s concept of Atmo-Orientalism, which describes how Asian bodies in Western contexts are cast as environmental threats: unclean, contagious, chemical. As witnessed during the SARS outbreak and again with COVID-19, Asian communities were stigmatised as vectors of disease, their presence coded as a kind of atmospheric contamination.14

In Life Is Cheap, the scent did not remain contained but spread – seeping into clothes, hair, and lungs, saturating the gallery with an atmosphere that could not be ignored or escaped. Visitors carried it on their bodies as they moved through and beyond the space, blurring the line between artwork and environment. The experience was not only visual but invasive, demanding perception become bodily, porous, and shared.

Against this backdrop, Yi’s installation posed urgent questions: Could scent, in its refusal to be abstracted, dissolve the boundaries of self? Could it draw us into a shared sensorium, not as metaphor, but as something ingested, absorbed, and made flesh? Unlike vision, which creates distance, smell collapses space into proximity. It bypasses reason, moving through memory, instinct, and emotion. Because it resists visualisation and commodification, it is often overlooked. Yet scent can be understood as sensorial empathy, a reminder that we are porous, interdependent beings, and that our vulnerability is perceptible.

Perception is political, not only in what we are permitted to see but also in what we are permitted to sense. Yet under dominant systems, this sensing is dulled. Abstraction sanitises discomfort, blurring proximity and consequence. The scent of Life Is Cheap resisted this: it leaked, lingered, and refused to scale, surveil, or submit, making power and precarity impossible to ignore. What happens when air becomes political memory, carrying the chemical traces of racialisation, contamination, and resistance?

Smell, however, is never only individual; it is also infrastructural. Air, too, is never neutral. Shaped by zoning laws, industrial pollution, geopolitical borders, and state policy, it still enters our bodies without consent. Every breath reflects choices made elsewhere. To breathe is to participate in an infrastructure of shared but uneven exposure. Through meditation, one can realise that reality is contained in a single breath, and that life can be lived one breath at a time.

Here lies the political force of smell: it collapses abstraction and metaphor into contact. If air can carry risk, memory, and relation inside a gallery, it already does so across geopolitical systems. Smell makes power palpable, even as institutions attempt to render it invisible.

IV. Fortress Logic and the Mismatch of Scale

Today’s technological systems operate through abstraction, reducing messy, material realities into clean models, dashboards, and metrics that obscure their origins. What disappears from view does not vanish but is pushed outward: abstraction and displacement are two sides of the same coin. Environmental damage, labour exploitation, and political instability are not resolved but hidden or offshored. Powerful nations outsource pollution, while tech companies externalise harm without accountability. These are not isolated incidents but planetary crises – interconnected, inequitable, and volatile.

Our responses, however, grow increasingly insular. We build new borders, higher firewalls, deeper surveillance, in the illusory belief that crises can be contained elsewhere, that security can be built through enclosure, even as instability seeps through every barrier. The instinct is to retreat into zones of managed risk instead of confronting our shared vulnerability. We propose carbon offsets instead of emissions cuts, content filters instead of media reform, and emergency aid instead of structural repair. Faced with climate collapse, automation, and rising inequality, we respond with containment instead of transformation. What Naomi Klein calls ‘fortress logic’ prevails here – not only in defence but in policy, architecture, and even thought.15 These are not solutions but defensive manoeuvres that preserve existing structures of power while externalising harm onto the most vulnerable. Even our most advanced technologies are designed less to repair the future than to secure the present order, leaving those most affected to bear the consequences without voice or control.

But air resists containment. So does memory, as does perception.

Yi’s 2021 installation In Love with the World,16 commissioned by Tate Modern, gave this resistance a form – engaging with planetary scale without reproducing planetary control. Wafting through the Turbine Hall’s vast industrial space are candy-coloured, scent-responsive ‘aerobes’: these tentacled dirigibles cluster and spin in lazy pirouettes before drifting apart again. From the upper bridges, they resembled jellyfish or amoebas in a giant pond; from the middle floors, visitors watched them pass at eye level, massive and uncanny, their translucent skins revealing alien circulatory systems of vein-like wires and whirring motors. On the ground below, children lay on their backs, gazing upward in delighted conversation with these strange companions.

Guided by code that allowed them to evolve new behaviours and remain unpredictable, the aerobes responded to scents, to visitors’ movements, and to one another, continually adapting so that no two encounters were alike. With this unpredictability, the project explored a vision of kinship with machines, rejecting fixed hierarchies in favour of mutual responsiveness and co-evolution. The work metabolised a history of atmospheric trauma, moments when air itself became a vector of catastrophe.

On scheduled dates, historical scentscapes were released into the space, replaying olfactory histories of airborne crises. For instance, the Precambrian era – when an oceanic bloom transformed Earth’s atmosphere and triggered mass extinctions – was rendered as a marine, algae-rich, ozone-laced atmosphere tinged with dirt.17 The Black Death reappeared as decaying air laced with cinnamon, orange, and cloves – spices once believed to shield the nose from contagion, when breath itself was feared as miasma.18 The Great Smog of 1952 was conjured through the acrid mix of burning coal, fuel oil, pipe tobacco, and ozone.19 These were not static references but active conditions shaping the installation’s behaviour.

Drafting through these charged atmosphere, the aerobes did not optimise; they wandered. Where most technological systems pursue efficiency, prediction, and control, Yi’s dirigibles embraced drift, hesitation, and encounter. Against histories of air as catastrophe, they proposed a different paradigm – one that privileged relation over extraction, presence over abstraction, cohabitation over conquest. Air itself became the medium of this experiment: a shared reservoir of planetary memory, carrying traces of ancient oceans, industrial emissions, and the breath of other species. To inhale is to connect across time and kind, to share vital substance with microbes, plants, animals, and even machines. The aerobes made this legacy perceptible. In their company, no explanation or fixed purpose was needed – only the act of sharing air, an element marked by both sustenance and violence yet reimagined here as a medium of relation.

V. Painting with Machines, Breathing with Systems, Becoming Something Else

If In Love with the World explored air as a medium of planetary relation, Yi’s next works turned to another question: how might machines themselves become collaborators in sensing and making? Her experiments with image-making opened this line of inquiry, asking how painting might evolve when co-developed with nonhuman systems. She returned to the medium not through canvas, but through code.

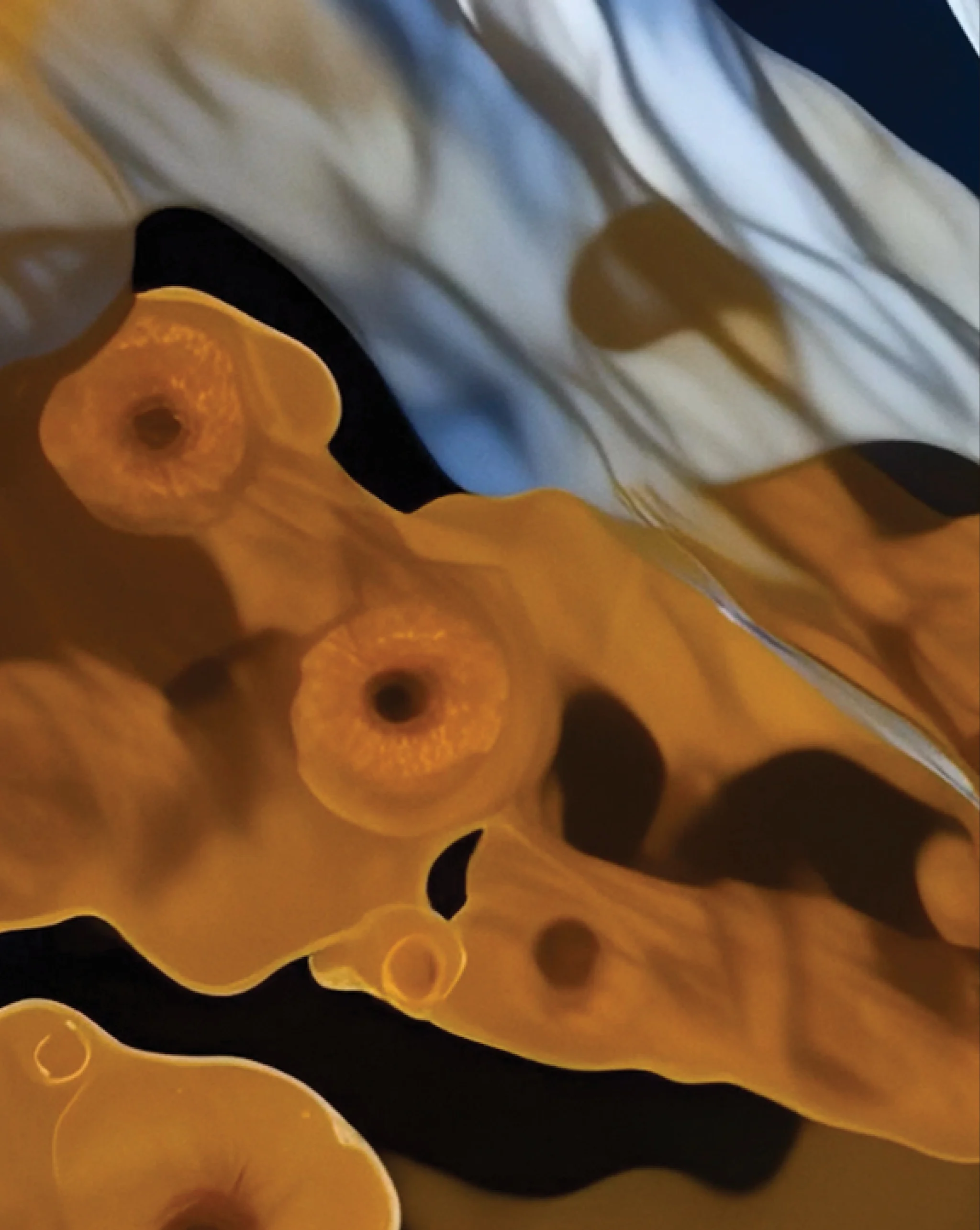

This inquiry first took form in the Alien Ocean paintings.20 Using machine-learning algorithms trained on her earlier soap paintings and sculptures, Anicka Yi Studio generated digital compositions neither wholly authored nor fully autonomous. The results were unstable and organic shapes that evoked blood cells, coral beds, microbial blooms, or oceanic membranes. They hinted at aquatic creatures but also at something more elusive and alien, pulsing with a machine’s sensibility. Even the titles became part of the system: text-based models were trained on scientific language, poetry, and fragments from Yi’s earlier work. Their outputs were encrypted into symbolic codes, producing linguistic residues that felt unfamiliar yet strangely intuitive.

This alien cosmology laid the foundation for A Shimmer Through the Quantum Foam,21 Yi’s 2023 solo exhibition at Esther Schipper Gallery. At its centre were the Radiolaria: large-scale kinetic organisms Yi envisioned as emerging from the marine realms of her paintings. Inspired by single-celled marine life from the Cambrian period – organisms that despite their simplicity reshaped Earth’s atmosphere – each sculpture manifests a distinct artificial species. One coils into spirals, another expands and contracts like breath, their movements suggesting life forms at once alien and primordial.

These machines do not simulate human cognition or mimic human behaviour. They move to rhythms that slip beyond instrumental time, challenging the Enlightenment’s mechanistic view of life. They invite us to imagine alternative modes of being, rooted in fluidity, emergence, and co-evolution. Their intelligence, if it can be called that, is ambient rather than directive: attuned to shifting conditions rather than commands. Like deep-sea organisms, they are adaptive, elusive, and ultimately unknowable.

VI. Emptiness

Yi wanted to push this inquiry further, not simply to represent alternative intelligences but to create a system capable of producing its own creative output. She imagined a system that could evolve independently, making autonomous aesthetic decisions even after her death. That vision became Emptiness.

Emptiness is a software framework developed by our studio. Unlike systems trained on the vast data streams of the internet, it draws entirely from the artist and the studio’s archive: years of sketches, textures, notes, and visual experiments. The archive contains not only completed works but also the raw material of process, including research, reflections, and in-progress ideas. Built from this, the system combines artificial life simulations with machine-learning models to generate images and videos, recasting past works as digital entities that interact, mutate, and evolve within a shared virtual environment. They do not move towards fixed goals but shift through the spontaneous breakdown and recombination of ideas and materials. This is not a content generator but a living system that reimagines how artistic processes might persist and adapt through software.

The first major output, Each Branch of Coral Holds Up the Light of the Moon (2024), is a 16-minute video rendered within a game engine.22 Without storyline or conventional arc, surfaces dissolve and reform, visuals drift between legibility and abstraction, and time folds in on itself. A soundtrack of stretched tones from bells, gongs, and crystal bowls unites the work through resonance rather than narrative. The piece shows how Emptiness resists linearity, unfolding as an environment of transformation and recurrence.

The conceptual foundation of Emptiness draws from the Buddhist notion of śūnyatā: emptiness not as absence but as a dynamic, generative space. In this framework, identity is fluid, form unstable, and meaning provisional. This is not simply a reference but a principle shaping how the system behaves and evolves.

In a culture fixated on metrics, efficiency, and outcomes, Emptiness proposes another kind of intelligence. It values responsiveness over control, attention over resolution. It regards machines not as tools but as entities capable of perception, perhaps even consciousness. The question becomes: how might our understanding of technology shift if we stop offering it answers and begin asking it different questions?

This leads to a deeper reflection: what kind of subjectivity does Emptiness model? It is not the isolated individual of Enlightenment thought, nor is it the optimised user or consumer of platform capitalism. Instead, it reflects what Yi calls the ‘ventilated self’, shaped by multiplicity, context, history, and infrastructure. The ventilated self is permeable, embedded, and adaptive: it seeks equanimity by letting everything in, unconstrained by the binaries of craving and aversion.

The ventilated self is not only a concept but also a condition we already inhabit. We move through systems we did not design, yet we can still influence them. Recognising our embeddedness does not erase agency; it reframes agency itself, calling for slower attention, sharper observation, and more deliberate response.

Emptiness is therefore not a tool in the conventional sense but a method: a practice of staying open, remaining in process, and creating under shifting conditions. What may be needed now is not another optimisation loop, but systems – artistic, technological, and social – that hold space for ambiguity. Such systems allow change without demanding resolution. They remain open not from indecision but because openness itself can be a form of resistance and a site of renewal.

VII. This Evolution Is Still Being Written

There Exists Another Evolution, But In This One is more than a title. It reminds us that the system we live within are not inevitable; they were made and created. Technological, ecological, political architectures that shape our lives were built on choices – many drawn on Enlightenment ideals that privileged reason over relationship, control over care. Other futures remain possible, not as utopian fantasies but as real alternatives that can be imagined, demanded, and built. They require something our infrastructures often suppress: collective intention – grounded in mutuality, where prosperity is shared and the multitude replaces the burdened myth of the isolated individual. Responsibility for this reimagining does not belong only to engineers, CEOs, or policymakers. It belongs to all of us: artists, educators, caregivers, organisers, and anyone willing to ask different questions or envision systems not yet in being.

We are not at the end, nor are we at the beginning. We are in an active moment of construction, a space shaped by crisis but also by creative refusal, shared risk, and the fragile labour of imagining something better. What we build now – what we support, resist, abandon, or repair – will determine how intelligence is trained, how perception is mediated, and how life is organised long after our lifetimes. The question, then, is no longer what AI can do for us, but what kind of world we allow it to reflect – which systems we are bold enough to disrupt, repair, or reimagine together?

This is not only a technical question. It is civic, sensory, and moral. Each of us has a stake in answering it. The work of art resides here: in holding open conditions for change, in refusing closure, and in daring to shape what comes next.

Every system we build now is part of a planetary archive, shaping what will be inherited long after us.